In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, policy makers approved trillions in new spending. Around $12 trillion to be more precise. These are big numbers. To put that in perspective, that’s $36,000 for every man, woman and child in the United States.

I hope to explore these numbers in the next few weeks, so if you’re interested, subscribe below.

I’m old enough to remember the controversy surrounding the 2008 bail outs. It was kind of a big deal. Policy makers allocated $700 billion to buy assets, although they only spent $426 billion and recovered $441 billion. The money was to be used to buy toxic assets in order to recapitalize the banks to avoid a credit crisis.

Many interpreted this as “heads I win, tails you lose” capitalism, where officials were rewarding risky behavior by the banks by acting as a backstop. However, some of these asset prices recovered and the administrating agency was able to resell the assets as a profit. It’s pretty clear now as it was then that this was just a way to recapitalize the banks and amounted to a huge transfer of wealth to legacy institutions.

I was not surprised to find $800 billion in the Covid relief package allocated for Federal Reserve purchases of mortgage backed securities (primarily agency mortgage backed securities and commercial mortgage backed securities). The Federal Reserve has a mandate to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and the ensure the stability of the financial system. You could say that 2008 bail out was different since it was rewarding risky behavior, and this situation wasn’t the fault of the banks. But this still amounts to a huge transfer to the banks.

How does this work?

In the US, when a bank gives someone a mortgage, it often gets insured by one of three pseudo government agencies: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae. The holder of the mortgage claim is now ensured against losses in case the borrower can’t pay her mortgage. The borrower presumably get a lower rate, although this isn’t always the case. This is an agency mortgage backed security (agency MBS). There is also a commercial equivalent of this.

Note that the above applies to who holds the mortgage claim. This does not mean the party that services your mortgage (the person you write checks to). That function is usually managed by a completely separate uninterested party (the servicer). The servicer usually receives a percentage of the mortgage payment and sticks around for the life of the loan, regardless who owns the underlying claim.

So when the Federal Reserve buys mortgages to “provide powerful support for the flow of credit to American families and businesses”, it doesn’t mean it’s supporting homeowners. The second, third and fourth order effects may trickle down to struggling home owners affected by Covid restrictions. But it’s primarily a transfer of money to existing agency bond holders.

To put these numbers in perspective, there are about 89 million owner occupied units in the US. The $800 billion used for agency repurchases would amount to nearly $9,000 for every homeowner in America. The median mortgage payment in America is ~$1,100 so this would amount to ~8 months of mortgage payments for all American homeowners, including paying down the balance!

Instead, we went the roundabout way of transferring money to banks by buying agency mortgages.

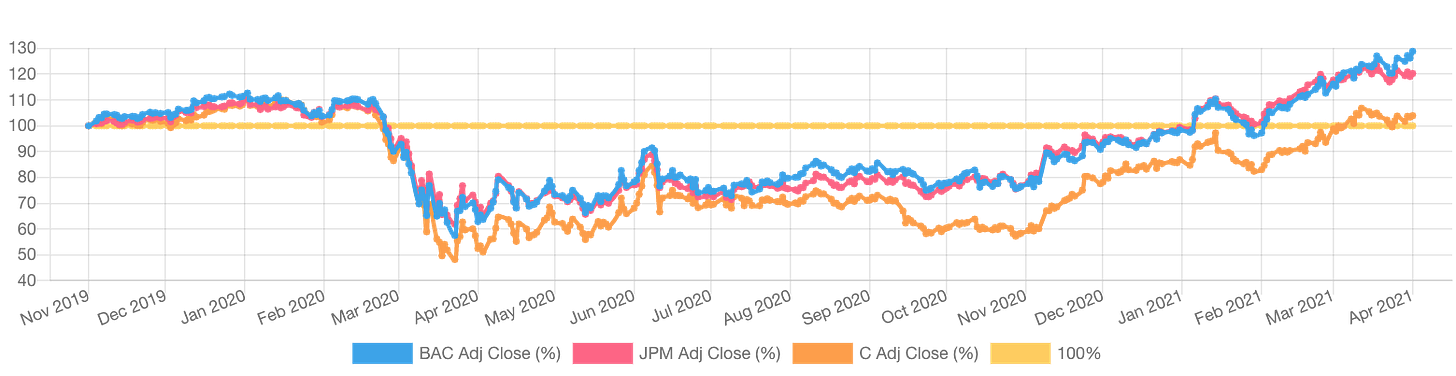

Who owns agency MBS anyway? Around 36% is held by the 5 major banks and 15% is foreign banks and governments (mostly China and Japan). Which helps explain why bank stock prices are up as much as 30% since November 2019:

Did it work?

Volume of agency mortgages made has certainly increased. Home ownership rate ticked up slightly, but the primary beneficiaries were existing homeowners who refinanced their mortgages (myself included). And home prices are up 10% since the pandemic which is … good I guess?

As an aside, framing an issue is always interesting to me. “Home values increasing” sounds better than “housing becoming more unaffordable”. Ideally the Federal Reserve should promote “price stability”, but their policies often amount to re-inflating asset prices that benefit existing asset holders.

So overall it was good for existing homeowners as prices shot up partially due to lower rates. It was good for banks because it was pretty much a direct transfer. It was bad for renters as median rent prices have gone up, although certain cities have crashed.

There might be a misunderstanding of what the goals are. Let's read what the Fed says and writes.

Fed buys "... treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions."

There are two goals in that sentence:

(1) "market functioning" means liquidity, the ability to buy and sell assets without affecting price significantly. Fed assures that there is a buyer for the assets with a reasonable price. (how they determine 'fair' is nuanced, interesting reading).

(2) "effective transmission of monetary policy". Monetary policy means control of the money supply. When Fed buys MBS from the market, the seller gets the money. Now the seller must decide what to do with the money. Consume (good), invest (good), keep in money like assets (accept very low return).

ps. Fractional reserve banking has not been the main money supply mechanism for a over a decade. OMO is used instead.