Taxing unrealized capital gains and shifting marginal tax brackets

There are no taxes that affect only billionaires, and that's by design

Senate Finance Chair Ron Wyden is proposing a tax on unrealized capital gains. The measure proposes taxing people above a certain wealth or income on stock appreciation even if they haven’t sold it yet.

This means if you own a company that does well on paper, you’ll owe a tax bill every year, likely forcing you to sell part of your company to pay the taxes. If it goes down, you can carry that over and offset future taxes owed up to three years (way too short in my opinion).

For illiquid assets such as real estate, you won’t be taxed every year since appraisal is difficult, but when you do sell, you’ll pay a deferral charge meant to replicate the interest you would have paid (capped at 49%).

But don’t worry, it only applies to billionaires. Literal billionaires:

Wyden's draft legislation would apply a new tax, beginning in 2022, for individuals with at least $1 billion in assets or $100 million annual income in three straight taxable years. It would apply to about 700 people, according to Wyden’s office.

That’s all well and good, until you try to think of other taxes that kick in at such a high level.

Shifting tax brackets

You often hear about top marginal tax rates being up to 90% in the US, and its true. The last time we saw marginal tax rates in the 90% range was in 1963. The top rate was 91% starting at $400,000, or $3.58 million in 2021 dollars.

Here’s the rate for 1963

The median family income in 1963 was around $6,300 so their effective marginal tax rate was 21.76%.

Today’s federal tax rates are much lower across the board but the top bracket starts around $628,000:

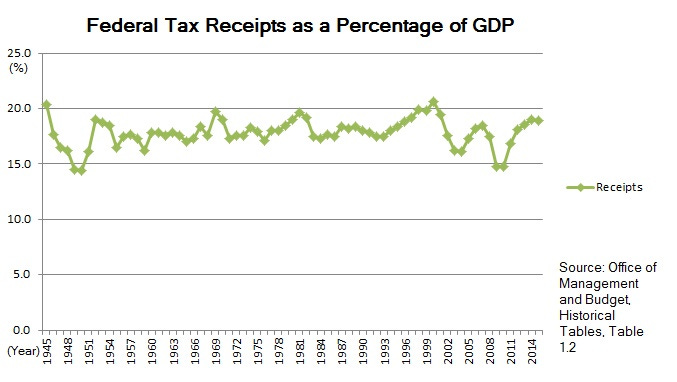

In-between the tax rates varied but the upper brackets have been coming down. But the rate doesn’t have that much of an impact on tax revenue collected as a percent of GDP. Whether the top rates were 90% or 37%, federal tax receipts a percentage of GDP have remained relatively steady at around 18%

What does this have to do with taxing un-realized gains

You don’t see any taxes that target only billionaires, so I’m skeptical that this tax will continue to only affect the extremely wealthy. New taxes usually get introduced as only affecting a tiny number of people, but then the brackets creep down. Take the federal estate tax. It starts kicking in with an estate of $11.7 million. Sure most people don’t have an estate of that size, but that’s not an absurd amount of wealth to accrue in a lifetime. Some states have an inheritance tax that starts kicking in a lot earlier, sometimes as little as $1 million.

Or consider alternative minimum tax (AMT). It went into effect in 1970 and was meant to capture only the very well off. By 2017, 5.2 million housholds were affected by it. Today that number is around 200,000 but that’s only due to the restrictions on deducting state and local taxes (SALT) when calculting income for federal taxes.

The current administration is even trying to make it so banks have to report money flows of accounts with at least $600 in annual cash flows. These people are hardly billionaires.

Introducing a new kind of tax is difficult. It’s a lot easier to move brackets around after it has been introduced. There are no taxes that affect only billionaires, and that’s by design; there aren’t a lot of billionaires out there and they have the means and incentives to avoid these kinds of taxes. So the brackets move down over time to capture a larger base.

And that’s fine. You could believe that we should tax mere millionaires on their unrealized capital gains. But don’t tell me how this new tax will only affect a few hundred folks over the long run and be a big windfall to everyone else.