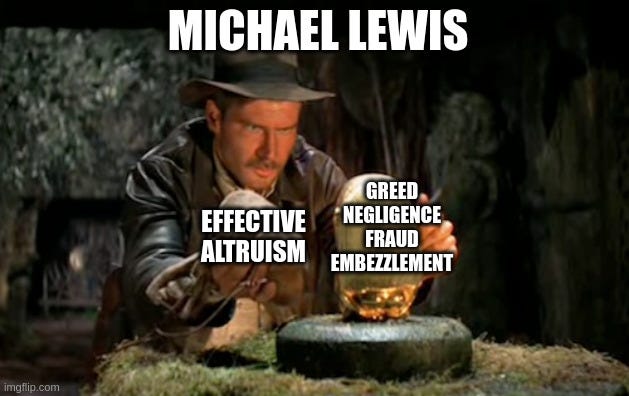

Michael Lewis, FTX and Effective Altruism as a MacGuffin

These effective altruists were neither effective nor altruistic

Michael Lewis’ book Going Infinite promises an intimate look into the meteoric rise of FTX and its mysterious founder Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF). Lewis was granted incredible access, which led to some insights into the characters. But ultimately the charm wanes as the author refuses to cast a critical eye on its subjects or ask basic questions about everything going on. Lewis’ focus on effective altruism, a philosophy that advocates for using reasoning to drive charitable works, is also at best a distraction and at worse a major cope on Lewis’ part.

Effective altruism as a MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is an object, device, or event that is necessary to the plot and the motivation of the characters, but insignificant, unimportant, or irrelevant in itself. In the case of Going Infinite, effective altruism was the MacGuffin: an ever-present stated motivation for everyone involved that turned out to be entirely vapid.

From the prologue, you can tell Lewis has bought in to everything SBF was selling, then and now. Lewis ties everything back to effective altruism, the purposed philosophy SBF and many around him adhere to. The term “effective altruism” and its derivatives are used 78 times in the book.

SBF is drawn to effective altruism early in his life as it appeals to his logical and reasoning nature. It leads to some truly cringe passages. Here’s SBF on abortion:

SBF: There are lots of good reasons why murder is usually a really bad thing: you cause distress to the friends and family of the murdered, you cause society to lose a potentially valuable member in which it has already invested a lot of food and education and resources, and you take away the life of a person who had already invested a lot into it. But none of those apply to abortion. In fact, if you think about the actual consequences of an abortion, except for the distress caused to the parents (which they’re in the best position to evaluate), there are few differences from if the fetus had never been conceived in the first place. In other words, to a utilitarian abortion looks a lot like birth control. In the end murder is just a word and what’s important isn’t whether you try to apply the word to a situation but the facts of the situation that caused you to describe it as murder in the first place. And in the case of abortion few of the things that make murder so bad apply.

Effective altruism drives everything SBF does. It’s not that SBF cares about people. He just cares about hypothetical math puzzles. Here’s Lewis on the matter:

You might think that people who had sacrificed fame and fortune to save poor children in Africa would rebel at the idea of moving on from poor children in Africa to future children in another galaxy. They didn’t, not really—which tells you something about the role of ordinary human feeling in the movement. It didn’t matter. What mattered was the math. Effective altruism never got its emotional charge from the places that charged ordinary philanthropy. It was always fueled by a cool lust for the most logical way to lead a good life.

Ability to solve puzzles is an underrated skill to have

SBF’s skill at puzzles got him far in life and landed him a coveted role as a trader at Jane Street. The Jane Street interview consisted of a barrage of gambling scenarios where candidates had to manage their way around an increasingly complex series of wagers. Candidates had to end the day up a considerable amount to be considered successful.

This part of the book was interesting. SBF did well at Jane Street, although it wasn’t enough to keep him around:

They’d paid him $300,000 after his first year, $600,000 after his second year, and, after his third year, when he was twenty-five years old, were about to hand him a bonus of $1 million.

Lewis does mention that SBF was responsible for Jane Street’s largest ever single loss when he orchestrated a sophisticated exit poll tracking system to try to get a jump on the 2016 US presidential election. The underlying assumption was “orange man bad for markets”, and SBF was able to determine the outcome earlier than most, being able to establish a short position before others. However, the strategy didn’t work as shortly after Trump’s win was inevitable, the market collectively decided “orange man not so bad” and the trade turned against him. The total loss was around $300 million on a single trade.

Jane Street execs didn’t care so much at the large loss. It was par for the course. Take large bets based on an edge, pray for the best and carry on.

Life after Jane Street

SBF left Jane Street shortly after, using his wealth and frugal lifestyle to launch Alameda, a crypto prop shop. Lewis uses effective altruism to explain why anyone would leave a place like Jane Street for such a big gamble. But SBF has decided to try maximize his wealth. And since he thinks in probabilistic terms, a 1% chance of $1 billion is better than being a single digits millionaire.

But realistically, you don’t need an elaborate theory as why a young, intelligent man would try to strike out on his own.

The rest of the discussion about effective altruism was just boring and didn’t offer any insight into the characters. Lewis even admits that the effective altruists were surprisingly cut throat about money, which is odd considering all their money would theoretically go to the same EA darling charities.

Here is a typical passage of “shucks, oh look at those effective altruists!”

Ryan had paid $15 million for it and assumed that Sam would live in it. Sam had taken one look at it, seen that some of its bedrooms were bigger than the others, and decided he’d instead take the Orchid penthouse, where he and the other effective altruists could live in virtually identical conditions.

Nevermind that blowing $15 million on a vacant apartment is less than effective.

Or here’s another one of those “look at those little rascals that just want to save the world” moments:

Someone snapped a close-up of his feet under the table: the laces of his new dress shoes were still swaddled and gathered off to one side, as they come in the box. Someone must have handed him the shoes and said, without further instruction, “You should put these on.”

But surely these effective altruists care about their charitable giving, right?

But even when it comes to the core tenant of effective altruism, the group fell flat. Sure they donated some money, but they didn’t really care about the details:

Over the previous six months, one hundred people with deep knowledge of pandemic prevention and artificial intelligence had received an email from FTX that said, in effect: Hey, you don’t know us, but here’s a million dollars, no strings attached. Your job is to give it away as effectively as you can. The FTX Foundation, started in early 2021, would track what these people did with their million dollars, but only to determine if they should be given even more. “We try not to be very judgy once they have the money,” said Sam. “But maybe we won’t be reupping them.” The hope was, first, that these people on the ground would know better than anyone what to do with the money and, second, that some people might actually have a genius for giving away money. “It’s trying to blast through the hesitation,” said Sam. “The default to inaction.”

You see what they did there? They offloaded the problem and said to give it away effectively. Why has no one ever thought of this?

SBF doesn’t care or have any original ideas about charitable giving. The “effective altruists” best idea is find 100 people and give them a lot of money no strings attached. There is no rigorous evidence based methodology effective altruism would demand. It’s all bullshit, and Lewis never thinks to question it.

Sin of omission

Even when confronted directly, Lewis refuses to consider that the effective altruism framing by SBF and others might be bullshit. In an interview with Vox, SBF casually mentions as much. Lewis was even there when SBF gave that interview, but you wouldn’t know it as it’s nowhere in the book. Why? Lewis explains:

Time: You don’t mention the infamous Vox interview, in which Bankman-Fried says “f-ck regulators” and seemed to admit that his caring about ethics was at least partially an act.

Lewis: First, I was there, so that was weird. He was zonked out. But if you think he wasn’t an Effective Altruist, or that he didn’t care about that, you’re out of your mind. His whole life was wrapped up in that. I sat through endless meetings with these people; endless discussions with his Effective Altruist colleagues

Lewis doesn’t trust the reader to make up his own mind. He obviously knows you’d have to be crazy not be believe his narrative so why muddy the waters with this contradiction.

At this point Lewis is 100% bought in to the story. The narrative was obviously meant to be a hero’s journey of a group of rag-tag renegade effective altruists showing everyone the power of throwing away convention for a new approach. But fate had other plans.

Lewis on the defensive

Lewis got very defensive about criticism that he had gotten too close to the source. And interviews Lewis gave didn’t really help his case. In the Time interview, Lewis muses about how he thinks all the money might be there and even suggests that a jury would be better served reading his book than hearing the prosecution:

Time: During jury selection for the Bankman-Fried trial on Oct. 3, Judge Lewis Kaplan mentioned your interview on 60 Minutes, in which you contend that you do not believe Bankman-Fried knowingly stole customers' money. Several prospective jurors indicated they had seen the special. Do you hope that the jury reads your book [although they are forbidden from doing so]?

Lewis: I’d love for the jury to read the book. Mark Cohen [Sam Bankman-Fried’s lawyer] said this to me: “You get up, you tell one story, and they tell the other story, and the question is which story the jury believes.” I’m in a privileged position to tell a fuller story, without leaving out any of the nasty details. If I were a juror, I would rather hear my story than either defense or prosecution.

I'm just going to tell you the story as I see it, and then leave you the discretion that then you lynch him, acquit him, or don't know what to think of him. I don't want the jury thinking I left anything else they needed to know.

…

Time: But Judge Kaplan explicitly advised prospective jurors the opposite of your advice. “You are to look at no newspapers, listen to no press accounts, do no internet research,” he said.

Lewis: It’s a funny thing about the American criminal justice system, that they like people not to know very much. Historically, it wasn't always that way. There was once a sense that you should have a judgment by your peers who were kind of knowledgeable about the context and the situation.

In another interview, Lewis even compares an author with a competing book as being worse than SBF:

When I mentioned this anecdote over lunch, Mr. Lewis leaned forward. “Here you have a person who’s written a book, and he’s trying to torpedo a rival book before it comes out?” he said. “That’s shocking. Talk about corrupt! So who do I think is more skeevy, Sam or him? I’d have to think about that.” (“He’s a friend of yours, right?” Mr. Lewis added. Indeed, Mr. Faux and I have known each other since summer camp.)

Overall Going Infinite has its moments. I really enjoyed the first third of the book or so. But nothing was cast with a critical eye. Nothing was questioned and therefore nothing new was learned. You don’t even really discover any plausible explanation as to why FTX was successful or what made SBF effective to the extent that he was. Everything was taken as given. It was a real disappointment especially given Lewis’ talent for narrative and access.