When you give your money to a bank, they have to store a portion of that money in reserves at the Federal Reserve. And the Fed is nice enough to offer an interest rate for deposits.

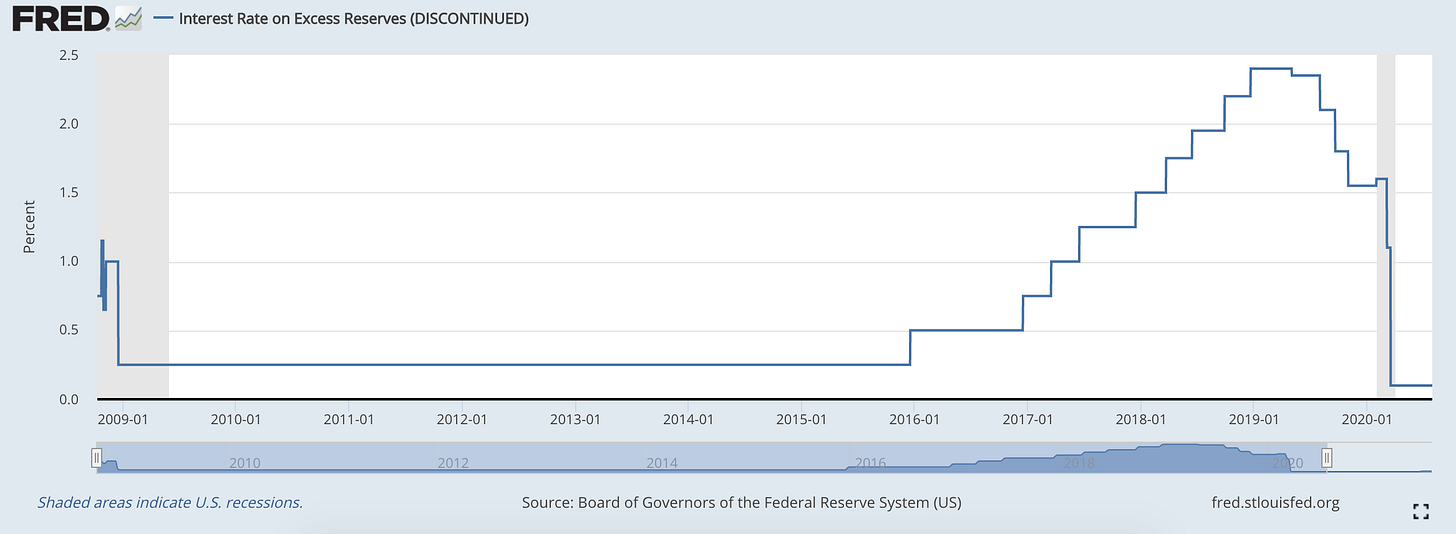

Interest on reserves began in response to the 2008 financial crisis as a backdoor subsidy to banks. They were around 1% in 2008 and then dropped to 0.5% from 2008 to end of 2015.

When rates started going up in 2016, interest on reserves also started going up. The relationship between interest rates and bank profitability is ambiguous since banks are simultaneously borrowers and lenders. But according to the Federal Reserve, for the most part its inversely related (e.g. higher interest rates are bad for banks). So the Federal Reserve decided to increase the backdoor subsidy in response to higher rates.

You may note that while the rate on excess reserves reached a peak of 2.4% in 2019, savings accounts didn’t keep up. Of course there are some fixed expenses with administering a savings account, but, from a bank perspective, this rate is a floor return on your deposit. Banks normally invest in higher returning activities with your money.

So why doesn’t someone open up a bank that keeps 100% of your deposits at the Federal Reserve and just pass along the interest rate the Federal Reserve is paying you? Why can’t you get the same rate as large banks on money that’s sitting there?

That’s the idea behind The Narrow Bank (TNB). I recommend Matt Levine’s piece on it from 2019.

The only problem is that the Federal Reserve prevented TNB from being eligible to receive interest on excess receives for the sin of not gambling with their customer’s deposits:

Among the concerns expressed in the ANPR are that entities with TNB’s business model have “the potential to complicate the implementation of monetary policy.” Such entities could potentially attract a large quantity of deposits and maintain very large balances at Federal Reserve Banks. This high demand for Federal Reserve Bank balances could require the Federal Reserve to accommodate this demand by expanding its balance sheet and the supply of reserves, which could complicate “the FOMC’s plans to reduce its balance sheet to the smallest level consistent with efficient and effective implementation of monetary policy.”

Basically, the subsidy wasn’t meant for consumers, it was meant for banks. Shame on this bank to think it can pass on the benefit and provide 100% reserves on people’s deposits.

The Federal Reserve also makes it explicit later in the brief:

The ANPR also sets forth concerns that the Board of Governors has about the effect a business model like TNB’s may have on financial stability and financial intermediation. (concluding that entities like TNB “likely would have negative stability effects on net”); (expressing concern that entities like TNB “could raise the costs of private financial intermediation”).

TNB may be bad for big banks. And because its bad for big banks, it could “make it difficult for the Federal Reserve to control short-term rates more broadly as a means of implementing monetary policy”.

Large banks could offer a competitive rate. The rate of excess deposits is the floor return for the banks: the minimum return they would expect to receive. All money they invest has to necessarily yield a bigger return, otherwise they would keep the deposits in reserves. So all it means is that the bank would have to share its subsidy.

Too big to fail doesn’t only mean that banks get bailed out when in trouble. It also means that nothing is allowed to threaten banks. Onerous regulations also prevent new competitors from entering the space, even if they would be objectively safer.

That’s why you saw the number of bank charters issued in the US drop in 2008:

What does this have to do with Coinbase?

It’s important to note that federal regulators aren’t only concerned with the welfare of consumers. They’re also concerned about the “financial system” as a whole. This means they have to consider the effects any financial products will have on legacy banks. Remember, big banks are too big to fail. And if its bad for banks that means it’ll “raise the cost of borrowing for small businesses” and “hurt the regulators ability to implement policy”.

So offering 4% interest rate on what’s essentially a savings account is bad for banks. So naturally regulators will take note. Will it sink large banks and dismantle financial institutions? Of course note, but neither would The Narrow Bank.

Is being bad for large banks the only reason why the SEC cares? Of course not. But you can bet that when something is bad for big banks, regulators will have their thumb on the scale when evaluating.